Earth Tycoon

by Simons Chase @slchase

[under construction]

A chapter, Macabre Riga, was published at the Dillydoun Review.

Geometry Lesson

A sun-coppered mist rose from the tidal saltmarsh. From the quiet of my bedroom window, I could see earth’s gumline in the crew-cut grass decked over the marsh’s fleshy mud. The marsh was veined in sinewy rills and runnels that threw wide arms of inky water around a vast hammock of marine life. There was a fast patter of small feet as the beach house swung into action. The sharp stab of frying bacon mingled with the taste of peppered cantaloupe—the flavor of my Southern accent. The sound of breaking glass created a temporary silence that reverberated through the adult and child precincts of the house. Someone yelled, “Okehya” from the kitchen, and our buoyant spirits resumed.

Our house, a variation of a mid-century Cape Cod shingle, had lots of rooms to suit a family and a rental market. It sat far enough from the center of town to be quiet, even during the height of summer, and it was close enough for easy bike trips to watch gulls surf the breeze around the draw bridge that separated the island from the mainland. The island had two sides. The expensive side was across the street from our house. The beach was over there past a row of houses that were situated on the dunes. The expansive saltmarsh behind the houses on our side of the street was a constant mystery to me and my burgeoning curiosity about the earth. Our galley kitchen, opalesced by day in the soft light of a stained-glass window rescued from a decaying church, lent the house a spicy, wild smell rising from the all-day dark boils on the iron-potted stove.

Some days we didn’t cross the street and walk past the Swinnerton’s house and through the dunes for an easy day body surfing, playing badminton and eating ham and swiss on seeded rye with a tiny sting of Coleman’s mustard. Instead, my father and younger brother and I would set out by boat from our dock to go net shrimping out in the unmapped habitat of that saltmarsh. This was my first memory of how the tension of a treeless landscape forced inward reflection. I encountered it again in subsequent odysseys into the Arabian desert and in the open-ocean, sailing to Bermuda. Youth barely differentiated these days, but from the point of view of maturity, moments of youthful brilliancies imposed a pattern on a life more powerful than the more recent adult memories that depended on reason alone. And also for days that rarely appear on the spectrum of possibilities for a child, like the pale and weightless mysteries of hospital hallways that followed months later, after this last day of its kind, that temporarily bleached my childhood.

I pushed the bow away from the dock with my foot and jumped in. The boat caught the canal’s current, and my father throttled the engine to point the bow up current. The narrowing channel compressed the fiery velvet of the terrain. We were quiet. Soon, my father turned the bow of the boat out of the straight channel, crossing into the natural curves of the marsh. A rain squall tinkled by, steaming exposed surfaces. A moist offshore air drew landward with the building up of afternoon terrestrial heat. Columns of towering cumulonimbus clouds marched in unison along the South Carolina coast, obscuring a pale day moon. Sunlight pierced the clouds’ doughy ramparts, swelling their silver boundaries. There was only brilliant blindness above the horizon and heart’s-blood black below in the low-tide trenches of the marsh.

Sun-dipped marsh wren soared in the shifting winds, never seen but always heard. They sounded off in a dry mewl and caw. Docile, far-off stares of yellow-eyed American oystercatchers betrayed the colossal natural abundance surrounding them, their wings folded, waiting for stirring urges and the truth of their aliveness: feeding at oyster bars and breeding. Curious laughing gull and clapper rail cut the sky. Their fleetness and their whispered murmurations wove into the landscape, no doubt shaped by the imposition of the hard lessons of economy and cooperation. They were their own environment. Their patience and patterns were traits volted through information nucleotides across thousands of years, powered by the constant ebb and flow of the tides. Now I understand their thin, stalky legs and webbed feet and how their different-shaped bills allowed the capture of food sources at non-competing depths of the mud: curved bill, short- and long-needle bill, and spoon-bill, the better for flight.

Saltmarshes are an ideal nursery for the hordes of exoskeletal creatures like shrimp. Tidal waters recede a few feet below the root zone of the grass, dissolving the desolation and sterility of the place, to unriddle the details of a hidden world of colorful fiddler crabs, snails, hermit crabs and a wide variety of worms. Here water becomes mud and mud becomes water with no indication of a phase transition: a sea of mud. An indifferent landscape that was both a hot, wet corpse and a plump, pink infant. At the bottom of this orchestra of life was the mud dog whelk housed in shells of Fibonacci-swirl. The snails consumed anything that death’s arrival rotted down on them.

Armored like shark’s teeth, oyster beds carpeted most firm marsh terrain. Only in occasional spots, where the fiercest rush of the tides created a smooth, sandy surface large enough to secure a boat, can you establish a beachhead and invade the temporary stillness with seining nets. Shrimp concentrated in the deeper basins of these creeks, and that’s where my father would take us to ply our long nets. The deeper mud zones were always a topic of conversation for us kids, scared of the embedded narratives: biting crabs and slithering snakes hidden in the mud, invisible aggressions and such. There was a constant challenge among us boys eager to defend our adolescent bravery by pretending to ignore the unknown swampy creatures hiding in the embalming mud.

The ebbing tidal flows swirled in eddies along the sand-rippled bottom of the channel signaling the nearness of low tide. The boat motor whined under a full throttle strain as we cut through the channels. The boat’s wake peeled off both sides of the stern and rolled up into the muddy grass before flopping back down into the channel. I curled my tongue in sympathy. A final burst of throttle pushed our boat up with a jolt, and my brother let out in involuntary cry, “Dad!” Fear stormed inside us both as the boat lurched forward onto the impermanent tongue of sand. Our base camp was the only thing not mud-black or oyster-covered for miles. We boys jumped out and pulled the bow of the boat up on the sand while my father cocked the engine up and turned it off. Then we untangled the net and spread it out on the white sand. Each end was secured to a vertical wooden pole. We mustered and rested in mechanical time. A black skimmer winged overhead and then sailed along the winding canal before tipping its wing to cut the glassy surface of the water, now still. It looked like the sound of a single ordered note of cello. The bird took an effortless turn around a corner and disappeared. The air was still and woolen, spiced with heat and earth. Insects trilled. There was no history there, no seasons, no shade, no fresh water, no drift of shadows – only the next tidal flow and some irresistible force that attracted us to the place.

The best time to deploy the seining net is when the water ebbs and stops and before it starts to flow, a peak period of about thirty minutes depending on wind conditions and the lunar cycle. The key to a big catch is to keep the bottom of the net on the bottom of the channel so the shrimp can be hauled up and collected on the clean sand. In our nervousness, my brother and I silently compromised and agreed to secure our end of the bargain by jamming the bottom of the wooden net pole down a few inches into the sand, at extreme angular peculiarity.

We acted together at dead low tide. My father waded into the dark undertow. He pivoted, and we deputized kids held our end at the water’s edge. I marveled at his animalness. His slim figure and muscular quickness lent him grace. Sometimes only his straining face and the glint of his ruby Citadel ring remained above the water’s surface. The herded shrimp leapt and snapped in every direction. Beads of perspiration flowed from his brow. My father’s face had a remoteness, and to see his danger made me anxious. His bone and flesh plowed away from our sandy oasis, net in tow under the invisible murk. He was easy to love – and easy to lose. The pull of the net forced us down a severe angle past the sand line and into the mud. Crude force clawed at our will to hold the line when the net was under the apex tension of my father’s exploration of the deepest water. My bent-nail leg quivered. Blisters erupted, and my sockets ripped with pain.

Aloof mariners, wings folded like a Buddha, watched us. They from the grassy mounds, glacial eyes and predatory grin, and us in our adversely possessed new land, where I belonged, out on the edge of living where every step was an adventure. The mud’s leathery grip tightened the longer we stood in one place. To escape the clamp of mud with our shoes attached we would point our toes down and with the upper leg repeat a downward push followed by an upward thrusting motion until water filled in the hole made by our foot and released the muddy grip with a squelch. Once immersed, our mud-fleck faces, salty tongues and squinty-eyed excitement met a constant swirl of life that was only partially visible from the surface. On that day, immersed in the details of my actions and reactions – no time to think – I was more like what my father believed me to be than what I believed me to be.

We sweated and grunted to slide the net up on the sand. Black water dissolved through the net’s woven geometric squares revealing hundreds of brown and red shrimp miracles, high and raw up on the sand. We pulled the net several more times, threw back the minnows and loaded the catch into several large buckets. Metastasizing tidal flows disappeared our mud scars at the shifting brink of the water line. The boat bobbed as if under the control of a mysterious force. In an instant we gathered gear and shrimp and bolted. Once we boys were safely in the boat, my father tugged a pair of utility gloves on his hands and headed over to the nearest oyster bed and tore away a clump of oysters. Before my father returned with the oysters, I leapt over the bow and buried my arm deep in the mud. Below a certain depth, the mud was cool and satiny. I grabbed a fistful, jumped back in the boat and covered my head and shoulders with a coating like a layer of protective lard. My brother did the same.

The view at low tide obscured dozens of narrow unseen channels running throughout this exposed earth environment and infinite horizon of grass. Sometimes the only way back to our dock was through trial-and-error navigation of the fortress of turns that seems at first to lead in the right direction but then suddenly switched back. Nature rewards patience. The odor at low tide was at first sulfurous and salty and eventually became floral and nostalgic. If it weren’t for the subtle sounds coming from mostly unseen fauna, the orchestra of insects, and wind and sun would have felt like an industrial process working on our soft bodies, pulling our pinkness into the watery jungle.

After motoring for a while my father slowed the boat and instructed my brother and me to grab a small buoy bobbing under the tow of a line in the channel. We pulled the rope up and hauled a crab trap into the boat. The boat engine powered up again. Spidery crabs danced. The sudden light of day caused one faction of crabs to war with the other at the opposite end of the trap and thus become locked stubbornly, claw-on-claw, until they all succumbed to the red-spiced cauldron in our kitchen. The three of us peered over the bow together, ignoring the low-hung gunwales. The patter-patter of the motor created a rhythm, as the mud-spattered boat tilted and bobbed, comically unsuited for the cargo’s weight. We were hungry. My father grinded a utility knife into the oyster’s adductor muscle. The oysters cracked open with a sound like cold eggs dropped in boiling water. Eyes ablaze in a muddy face, we slurped the oysters into our mouths, folding them back into darkness. The living sea biology poured out in me a satiating pulse of victory and quieted my hunger.

The zigzag rooftops of the houses that line the canal looked like toy houses arranged on a game board. Their windows glinted in the sunshine as we glided down the canal that was corrugated with private docks tethered with wooden walkways to sun-scorched lawns. We swung around to point the bow against the direction of the prevailing current, eased up to the dock, “Watch your fingers, boys,” and tied up. The boat, now unburdened of its load, bobbed in the current, banging gently against the dock’s rubber bumpers. Every pull of the boat line was an inane circular argument between the water current, the dock and the boat. The mud on the boat had dried in the sun in abstract resemblance of the chaos of the wild. My brother and I took the fresh water hose and cleaned the mud off the boat and off ourselves. In the distance a tiny fleck of a sail boat, wing-on-wing, slipped downwind towards the bay that eventually opened up to the deeper fathoms of the sea. We returned to our domesticity.

The first floor of the house was ten feet from the ground, “on stilts,” as they say. Only four wood-paneled outdoor shower stalls and an enclosed stairwell occupied the space under the house. The shower tops and bottoms were exposed. Rusty shower heads protruded over the top of each stall like dying metal flowers. Bathing suits drip-dried on nails. While in use, sun-stained feet slow danced in a circular pattern around the water flow. Steam rose over the top. The appearance of two pairs of adult feet under the same steamy shower head aroused hilarity, and my brothers and I would creep up to the shower stall to observe this oddity. Our heads peered around the corner, stacked by height, our faces shaped with curious smiles. There was a single shaded parking space under the house. The remaining sunless footprint was soft dirt and a keeper of ughyucky bugs. Flighty sparrows twitched and rollicked in dirt baths. A central switchback stair case connected all the floors of the house from the ground floor up. The kitchen and the large living room dominated the first floor. There were porches on both sides, East and West. They were less like columned verandas and more like screened porches. The East porch facing the ocean was slippery with dust except after a heavy rain.

When my father unlocked the house door at the top of the stairs on arrival each year at the beach, we would rush in, taking in the familiar sights and smells of the house. It was for me a moment of high exhilaration. I stormed the stairs, clear and precise, without even looking. At times, a mizzle of worry swept my face. Crooked was the melancholy of departure two weeks hence. A snap collision with the joy of raucous play. I loved being there among the seashells, the sound of the sea, the sand and the creatures that animate a feeling to find no end to this time. Yet conjured up were the dissolving words that signified our eventual departure. Packing and cleaning and my pleads for reprieve. The quiet power of those words emerged out of the future, uncoiling a landscape of dark emotion. I tried to pocket the toy of this little morrow-sorrow danger. The shadows shimmered in the lee of me. Those around me could plainly read my change in mood. No one in my family had the power to make us all quiet or afraid. There was no trauma, no darkness in the channels of our blood. The puny thoughts eventually receded and were finally ebbed away in the cleansing trials and explorations of the marsh.

Long strands of rope-wrapped floats hung like Christmas decorations along the spine of the high, carpentered ceiling of the family room. They were made of green and blue glass balls the size of honeydew melons and were draped in now-dusty fishnets. These hanging ornaments were originally used as floating supports for fishing nets or for marking navigation channels, and ours retained the visual imperfections common to glass making in the early years of the last century. Old wooden crab traps and weather-stained coastal navigation charts hung on rusty nails, iron driven into wood-paneled walls. Moody oil paintings skylighted other worlds. The largest one hung over the mantle, a tall clipper ship, sails ablaze in a gale, navigating an oily night of searing moonlight towards some distant shore of discovery. On either end of the mantle sat half-melted candles enclosed in large hurricane glass. An entire stuffed swordfish was mounted opposite the mantle, above the bank of double sliding doors that open to the East porch. The furniture was, “good enough for now”, except for a few upholstered straight back chairs that were loose ends from another house. A domed-top wooden chest with rusty hardware dozed in the corner, waiting for the play of hide-and-seek. There was a lamp of Scandinavian design standing in the darkest corner of the room. Multiple lights jutted out at different heights of a central bamboo stalk and projected oblique bulbshine. National Geographic magazines scattered across a wagon-wheel table with a glass top, their yellow covers composed, in a zebra-striped pattern, by the sun stains of long winter days when no one was around to organize them on a shelf. There were books and a pair of patriotic prints from World War II. An ornately-framed photo of a difficult-to-love aunt, now in cold old age, stood on a square table next to a proud starfish, hard and dry.

It was a joy to be in the house, not just for the promise of comfort as a basecamp after days out in the saltmarsh. There was a daily flow of people and little structure around our time. Cousins spent the night. Friends joined us for dinner on the West porch at sunset. We kids gamboled with my father in the den. Hugs were common with my mother, especially, since she cottoned to all my patterns and peculiar sensitivities, my ambiguities, compliant or rebellious. She understood, despite the frustration, why “Clean your room or else!” opened up my full-color preference for the “or else” that was too exciting and free for me to ignore. I noticed how my mother would say she took her (hard “k”) kids to the beach and protected her (soft “ch”) children from sunburn with lotion. Adding to the gloss was the ritual trip to the local amusement park, always on the last night of our visit, a distraction from the angst of departure.

The mood on the porch was leisurely. Chimes of laughter interrupted the pop and stew of conversation. The faces of my family and friends were alive, honeyed with satiety. I felt a charge of joy in them for my father, his playfulness, his kindness and ease of being. I have only a few flickers of his tender words now. What remains is his on-the-go actions and the energy of the emotional closeness he nurtured in those around him. I know this because these qualities are written in me, his roots and fibers shored on me. His words and actions were true and fixed like parallel lines. I want to believe in my imaginative understanding of his patterns that he fathered protective thoughts in me like, “hate is a mirror,” that I said to my children. My parents were in love, and though the weight of single-parenting us boys pushed my mother to the limits of our gunwales, she and we prevailed.

The sun settled down, now barely visible from the dinner table on the twilit West porch. A low amber sky colored red-blood the veins of the deep channels of the high-tide saltmarsh. At the end of those sunny, laborious days the delicate release of control arrived with sleepy, lust-lost tentacles. There was the supreme rotundity of seasoned shrimp, captured earlier that day in the thrilling hazards of those channels. They were the color of molten drops of sunset, flecked with a tiny tint of gold. Heads removed, piled high in bowls, the shrimp retained their intimacy and perfection even after the transition to food. Succotash. Potato salad. Corn on the cob. Tackled watermelon slices. A compromised brick of cheddar. Involuntary breathing. Me, asleep at the dinner table. Me, folded over my father’s two arms like a rolled carpet. You and me, up two flights of stairs.

My eyes slit as the day’s brightness peeled away into a mantle of mental darkness. You can never really get all the sand out of the beds of a beach house. Those tiny grains assaulted my sun-stroked skin, chafed me between the sheets, needled my blisters, amplified the bolts of muscular pain – and also delivered a snug bit of faint pleasure. My joints ached and tugged at me, demanding attention. My mouth buzzed with the sting of Old Bay seasoning. I reached for circumventing thoughts far away from my bed of nails. I wondered about all the creatures in that dark swamp, whether there was a parallel distress in their nightly foraging movements, in their diverse larval rhythms, in the effects of seasonality, and in the unification of dark sky and earth’s blackened flesh. A mound of those creatures was in my belly, stirred up by a final dark push through my murky insides, their resinous juices mingling with my own body, scratching from the inside to deny me peace. In these cloistral days of sand and seasoning I turned these creatures into dreams.

——————————

As an adult, I visited the Jardines de la Reina (Gardens of the Queen), a palm-fringed national park situated along Cuba’s Caribbean coast, where no man lives. A special circumstance offered me a weeks’ quarters aboard a live-aboard diving vessel that included one-on-one diving lessons. Being away from my wife and children was disorienting. Newly encountered questions paralleled a palpable drift in my daily habits and shifted the way I experienced time and opened up questions about natural theology that had attracted my curiosity since childhood.

My first sensation was the significance of my map coordinates (21°07’12.2”N 79°21’53”W). There sits a temporary, seasonal diving center, a floating village tethered to a point in time far in the past. 50 miles south of the fishing village of Jucaro, a windswept village itself teetering on the edge of the last century’s middle years, 21°07’12.2”N 79°21’53”W is actually anchored to a patch of sandy mangroves and coral that make up this archipelago, the subject of my exploration. The 75-mile-long spit of land is oriented East-West and sits precipitously on the edge of a 10,000-foot drop in the sea a short distance from its rocky shores. When Columbus encountered the archipelago on his second voyage in 1493, he named it to honor Queen Isabella of Spain, his financier. The distance traveled, combined with the disappointment (I suspect) in finding the land utterly useless in terms of animal husbandry, agriculture or gold mining, must have inspired the bold declaration of its “garden” quality. Safe in the knowledge that Queen Isabella would never set foot in her Caribbean garden, the contours of his narrative about the archipelago’s floral qualities seem to betray the reality and was instead closer to something like the shape of the archipelago itself – long and serpentine. I thought some aspects of living at the floating outpost must resonate with the experience of those ship-bound early explorers out on their frontier.

The archipelago looked virtually the same as it did when Columbus arrived – permanently innocent of humans. Today, not even a raw board cabin exists there. Experienced mariners of his time were said to plot their course by major star constellations, meaning Columbus was lost when he found and named the place. But his journey says more about the meridians of his ambitions than his navigation skills.

Water, wind and sun dissolved the modern day’s grid of predictability, and I found a rhythm shaped by the dominant force at the outpost, the pendulation of solar and oceanic cycles. Sleep depended on physical exertion, and hunger drew closer to my nutritional needs. By the third day, I had not worn shoes or clothes (other than bathing suits) in two days. The lack of any Internet connection healed my fractured attention and my addiction to its brash demands to shop for my identity. A nightly repertoire of wild sounds, different from the stop-time rhythm of the saltmarsh of my childhood, penetrated the boat’s hull. The scene remined me of the stories told by ancient mariners like those among Columbus’s crew; the pop, clink and ting of the sails’ rigging pounding against the mast, the frisson of sea wash and sargassum that was a constant reminder of the sea’s twin states, treachery and bounty, for those early explorers whose only distraction was roach water and cold oatmeal served twice a day – and the occasional grog to ward off mutiny.

More than 500 years of civilization had virtually eliminated the hazards of sea travel by the time of my journey to 20°24”12.2’N 78°55”26.5’E. In fact, I was not denied essential refreshment at any time during my trip. I became acutely aware of the culinary distinction between Maine lobster and Caribbean spiney lobster. These benthic carnivores – Panulirus argus, a marine crustacean – have a fossil record dating back to the Cretaceous period – about 140 million years. In fact, marine arthropods, which includes crustaceans, make up the largest single proportion of carbon weight in the animal kingdom living on earth. Today, Caribbean spiney lobster are both abundant and legal for catching in small numbers in the Gardens of Queen, a section of Cuba that potentate Raul Castro reserved for himself for a generation – his Cuban subjects forced under a hammer of brutal authority. Only one weekly boat of a dozen or so foreign visitors were permitted to explore a single spot of the vast, virgin reef that is too far offshore to be spoiled by nitrogen runoff, pollution or the scourge of mass tourism. Another pattern of brutality played out, ironically, in the same generation as Castro’s dictatorship; most of the Caribbean’s other coral regions have been cruise-shipped into rubble like soil turned to dirt.

The wind typically freshened out of the East during my nightwatching. Cuban flags popped smartly as if to celebrate. A total lack of light pollution made the night sky brilliant and mesmerizing. The night’s first feature was not a starscape but a wink from Venus.

The sun rose like a NASA launch video in slow motion. The water’s reflective quality concentrated the amber and white light in the vast zone surrounding the sky-open theatre. Nothing escaped the probing rays of the sun. On the wall just inside the ship’s dining room was a frayed, fading image of a man sitting in the sun with what looked like an Audubon society binocular case lying on the table next to his chair, the chair I was sitting in. His eyes squinted in strange resonance with my acetylene sun. I imagined if music were filling the cathedral-like scene in front of me with equal amplitude, the man in the image would be covering his ears, and smiling.

I soon learned why the Gardens of the Queen is considered to be among the best diving locations in the world – and certainly the best in the Caribbean. The depth profiles were numerous. There were shallow reefs and drop offs with spectacular walls filled with thriving flora and fauna. Shallow coral screes glinted like erupting rib bones under the undulating sea surface. Other areas contained a gently sloping shelf that bled into a slide towards the giant abyss. These areas formed a sort of water highway where sea creatures traversed the archipelago in a near still state, calculating their next feeding.

Evidence of Lévy walks (and Lévy flights) emerged decades ago when scientists recognized common foraging patterns in flying birds and swimming sharks that approximate the unordered scribblings of a child. Scientific advancement has since characterized these patterns as not random. They conform to a predictable statistical model and exist across different species of the animal kingdom. The most recent discovery is the empirical evidence that these rhythms are derived spontaneously, not from environmental signals. Worms that have had their central neuronal circuits severed display the same default pattern, meaning the signals are generated at a cellular level, in the absence of complex neurocircuitry. The same can be found in immune T-cell motility in human brains. The multitude of species that share evidence of Lévy walks in some cases have not had a common ancestor for 450 million years. Levy walks emerged innately, computed at a cellular level in almost all living things, suggesting instinctive problem-solving intelligence that likely predates the evolution of brains.

I wheeled myself backwards over the boat’s transom, through a surface splash, and as I cork-screwed downward, childhood memories abounded. Diving has the unique quality of putting the traveler closer to exploring than sightseeing. The technical aspects concentrate the mind on visual acuity and enhance perceptual sensitivity. The translucent world of the water, so long the carrier of human surface dwellers, revealed her nurtured fruit slowly to newly initiated divers like me. Little of this Eden-like bounty was known to the early explorers. Today, the more practiced divers hunt for rare images captured with the help of elaborate, tentacle-like lighting equipment. I learned, for the experienced divers, these images are like planted seeds to be harvested later. For me, the experience surfaced waves of rich memories from decades prior when there was a closeness to my living father and to nature.

The monstrous black depth loomed just over my shoulder. Perfecting my buoyancy allowed me to fly over and float into the features of the underwater world. There were whorls of rays, turtles, rare goliath grouper and sharped-toothed sharks. Endangered Elkhorn coral soared above a shallow seafloor, giving life to a universe of tiny living creatures. A Caribbean reef shark drifted by within a few feet of me. Its private eyes stared at nothing. I reached out and touched the skin of the shark down its length to its tapered tail. I followed the boundary line between the shark’s white bottom and grey top. The contour of this line was the same as the boundary between the dirt and the grass lawn underneath my childhood beach house. Looking from above, out of my window, I remembered looking down to see a rough yet assertive line shaped by the grass reaching for maximum coverage of the dirt under the house, provoked by thousands of passes of sunshine.

A diving companion came across a rare seahorse. Diver-waving me over to inspect the creature through his camera lens, I floated, effortlessly, over the shelf. I was in control of my biology, viewing through a lens this jewel that was no larger than my smallest finger. The seahorse possessed a person-sized sovereignty. The truth was in what I was seeing, and a network memories accompanied. I was observing by virtue of thought and emotion, seeing the way I think my father would want me to see. The gift I wanted to give him was the shape of his heart reflected in the harmony I perceived in the natural world. In this moment of supreme aliveness, I thought love is humanity’s highest expression of intelligence, requiring neither literacy nor numeracy but only earth’s abundant food and water. I was creating earth and a clade of interconnectedness in his green spirit.

Spectral sunlight filtered through sixty feet of clear water revealed the details of the seahorse’s patterns that were the intersection of beauty and exquisite roughness found in rusted iron or in a sea shell. I drew closer, dissolving into it, feeling not alone. The jagged lines and fractal shape of its tail suggested an ancient and familiar geometry. Thoughts from the voice in my head that was a spicy lump in my throat, said, as if to my father, “If man invented God, then man will destroy the earth.” Despite this corruption, new perspectives flowed. I was wonder and gratitude out there on the edge of existence. I had turned the swamp of my emotions and feeling into a garden, the way I know my father wanted for me.

Untitled

How clean was the lengthening shadow of the seven star Burj Al Arab Hotel, stretched out, totem-like, across the waveless Dubai coast. At forty stories above sea level and jutting out two hundred feet from the man-made coast, the hotel’s metal and glass exoskeleton glows amber against the slow-motion rocket launch of daily sunrises – those lurid blazes. A hard salty mist hangs in the air. Workers toil the beach down below, raking sand to mimic Saint Tropez. Royal palm trees validate the boundary line between beach sand and grass. Songless fronds hang from the palms to shade the coming afternoon sun.

I had been up most of the night, compressed by electronic trading options on the distant New York Stock Exchange, and now had to switch gears by stepping into the tactile reality of the weightless dirt and dust in the gilded sands of the wide-open desert. I still had some youthful urges that were not diminished by the burden of too much early success in some narrow spectrum of trendy commerce. This was honest work out on the frontier beyond the glitzy hotels – cranking cash out of old minerals. I could prove it by the microscopic travel dust that blasted into my interior spaces – my clothes, my body and even my toothbrush, invaded by the details of the desert. Dust, earth’s breathful revenge for aggressive commercialization of her rocks, uncoils upon the slightest perturbation, a fact I learned on regular visits to the actual mine site in nearby Jordan. Jordan’s Bedouin tribes people shoulder silence when they walk, and in the desert they stand in spontaneous testimony like tent poles, clean and spacious in the life of the earth. Excessive reserve is their style. Remote. Their arid faces trace subtle crevasses like the contours of tree bark. Yet when interaction is personal, I had learned, the Bedouins’ real aspect is familial and warm. heads enshrined in red and white utility cloths called keffiyeh. Around them, in their neighborhood, the geological violence from the hammer mill belches plumes of red dust, scratching the heat-shimmered sky, curling out in spindly trails from an unseen fire, squelching the brilliant silence. At a distance, the clocking tick tock sound of the mill spirals through the breeze, spilling time. Up close, the physical roars from the torn open earth stir up squalls of curiosity in the Bedouins whose desert fluency compels them to see the earthen plunderage as a symbol of opportunity, perhaps gifts from Allah, but denied like the lure of the smell of sizzling bacon. Dubai is different and out of proportion. The place thieves reality. The biography of Her textureless geological features coalesce towards two things, sand and sea. Despite the reprieve from the monotony of sand, the sea represents neither treachery nor bounty. Breezes only come at night, and Russian hookers only leave in the morning. In Dubai, nothing is produced and everything is sold.

With the shades and shadows of the early morning gone, I popped the pillow mint in my mouth and stepped out of the hotel’s entrance and into the teeth of an alien heat. Depending on the particulars of the route and the coordinates of the destination, my daily journey passes far beyond the skyscrapers. Instead, bushels of imported Sri Lankan workers, their blurred faces inflamed into work by some distant obligation, dominate the scene. There are other sights that border on sensations. Spastic funnels of wind-blown sand, tableaus of sound and brilliant light and, most memorable, the desert’s iconic symbol of travel, the camel. I grew up surrounded with by glossy snakes and birds and creek-bottom salamanders turtling over patches of wet bog, seeking the release of flowing water. The camels were toys framed by the desert, their fantastic bulk hurled across space by misty desert shimmers. In the late day sun they throw long shadows on the sand like thin-trunk trees with huge swaying canopies.

My professional boot camp, the study of developing country economics, transitioned to the theater of actual earth moving in a Middle East mining project after I completed graduate school and joined the senior ranks of a new commercial operation half way around the world. It was possibly the only true venture-back mining operation in the world if you consider the high probability of uncompensated risk and the rugged psychic landscape required to survive the depredations of commerce on one of earth’s few remaining frontiers. I was stepping into a landscape so lacking in personality that the ideas we inserted into it became our own possibilities. The Greeks called zeolites boiling rocks and the ancient fascination with this quality extended into modern times in the same way science eventually fills in for superstition. This special form of volcanic rock belongs to a tribe of hydrated aluminosilicates (more precisely, Phillipsite Zeolite), born out of rapidly cooling magmatic squirts of unfinished earth just below the surface in pimple-like volcanic vents scattered like tossed coins across a rocky desert landscape. The sharp elbows of shifting plate boundaries resulted in a vicious Oligocene feud about whether to make the crustal fault of Jordan’s rift valley rich in dry sand or rich in water. This went unresolved for millions of years until, suddenly, the east side of the valley lurched up – pushed by Africa – preventing the sea from flooding the area, and produced the lowest point on earth where bible-writing humans played and walked on water. Israel sits on one side of this split personality and the Arabs on the other. Breaching the normal rhythm of rock and roll land-shaping processes birthed the deep-earth volcanic tantrum and an orchestral blast of little mountainettes where our mine site was situated. The stirring up of these extreme forces no doubt manifested on humanity’s stage in the form of an equally hot theological cauldron we call the Middle East, the place we’re barley able to survive, dormant guns always on the edge of conflictual death. In today’s venture-geoscience-capital terms, this meant squeezing the right dot could yield a special form of zeolite, possessing not only great water-holding capacity (the source of its mythical boiling quality) but also a mineral endowed with a hexagonal molecular structure and an ionic charge that lends itself to exchanging ions in commercially viable ways – together with the magic of ever-diminishing unit production costs should demand tug consistently towards increasing volume. People exposed to these rhythms tended to exhibit strange behaviors, mostly related to the private language created around the numerous shared epiphanies that result from mineral speculation in remote environments with rocks that are indifferent as to their next move. A small founding team of three, including myself, formed bonds far beyond professional obligations, as the strangeness of far-off places tends to magnet affinities. Abe Dwairi, who held a doctorate in geochemistry from from a well-know British university, was a Muslim who drank cheap local beer out of a Coke can as a subtle tool for self-examination. And there was Jerry Zucker, a self-made billionaire from the United States, a man on a mission. Team building exercises flowed imaginatively, without the need for corporate-scripted exercises that too often side-step the deeper issues of personal vacancy and private murdered spirits among employees. They are built with empathy from the barriers of language, religious tradition and commercial uncertainty.

Jerry was a force of nature, something deep and flowing. Electromotive forces seemed to emanate from the dense and spiraling coils of his mind. To spend even a small amount of time with him was to witness an impossible thrust of information and a mental vectoring of vast experience, deep intelligence and a fluid imagination. Dots, people, industrial processes, financial statements, cunning uses for trapezoids and an occasional movie script coalesced into rivers of deal flow and intricate little streams of economic possibilities, always meeting at the highest possible points, always thinking at the top of his voice, always flashing from a young inner fire – a Forbes-list industrialist who had earned it by creating one of the world’s largest commercial behemoths. Jerry’s intelligence went way beyond social graces and feats of photographic memory, and if those two qualities were all you brought to the table, the conversation was going to be short. His real passion and unmistakable style was speculation. He thought about and acted on investments and, when not busy doing that, he built businesses, some of them large and global and some of them fascinating like the Chatterbait patent and a billion fish lures a year. Like the mining business in which we were engaged, opportunities emerge from unlikely places and have potential that is not apparent to a casual observer. He started out his life with virtually nothing. His first invention was made in the context of a high school science project, a revolutionary phase factor for Colinear Electromagnetic Waves, which was used as part of the first lunar landing module. For Jerry, money was a form of thinking and never an expression of ego.

My foot in the Dubai desert

Periodic geogligical surprises, like the magical rocks residing at our mine site in Jordan, reveal earth’s way of speculating. In fact, the volcanized desert (the kind of desert that does not exist in Dubai) is the Apple store of minerals. There is excellent lighting, ruthless minimalism and a need for imagination. How else could Basaltic rock, heaved up from deep earth pulses, sun-stroked and gravity-entangled, rapidly cool into crystallized minerals and then lie inert in a lifeless, treeless desert, where the sky ran out of water, on a speed-of-God 100-million-year journey of absurd irony to become a rain forest. Oozing ancient earthfire matured over millennials to produce something novel and valuable. In fact, if you compressed time from billions of years to just a few decades, you would discover the adventurous nature of earth’s minerals and the liquidating geological forces swirling around them. Life emerged from this kind of inert matter, from rocks, sand and salts, and through lifeless fundamental processes that relied on atomic level ion selection and purification and an as-yet unknown force shepherding spontaneous self-assembly. At room temperature, with no external force, these chemical processes occur naturally in zeolite through ion exchange, a molecular manipulation so simple as to mock our complex industrial processes. And moving up in scale from the molecular level to the physical level, a hidden depth of tiny cavities produces great internal surface areas with remarkable water-holding capacity. The whole natal package, the basaltic rock that you can crush with your bare hands, contains iron, magnesium and other life-affirming trace elements. Mineralium vitae. If there were ever a avant-garde mineral, this is it. More important, zeolite captured the meaning I projected on to it and reflected back building blocks, with a narrative capacity, metaphors and a time dimension.

The threads connecting earth’s geology to our biology remains a mystery beyond the basics, like the parent materials we humans are made of. These elements that give life to all that exists includes carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen, calcium, and phosphorus. Zeolites are just a temporary fleck on the much larger canvas of earthen mineral speculations that have been going on for billions of years. Earth’s early bio-geochemical musings likely relied on ion exchange mechanisms that echo today in neuronal voltage-gated ion channels, the central mechanism active in human brains, even in the glial cells that make up more than 90% of brain matter and that were once thought to be inert. From early man up until the present time, minerals have been mingling with humans’ daily activity and also telling stories of the deep past. Zircons, crystalline minerals containing silicon, oxygen, zirconium and sometimes other elements, form inside magma and last forever. Their relentless memory goes all the way back. In some cases, their carbon-isotope ratios implicate biological forces at work yielding a narrative three and a half billion years old. Another rocky relation is igneous rock, which forms when molten magmatic material cools so rapidly that atoms are unable to arrange into a crystalline structure. In some ways igneous is the anagramatical cousin of zeolite, lacking zeolite’s light and breezy personality despite being born in the same places. Earth rearranges molecular structures with time-dependent processes instead of letters in her alchemy of earthen anagrams. Deprived of its cousins’ sparkle, igneous has a distinctive shiny appearance that gives the a “volcanic glass” quality and is blackened by small amounts of iron and other impurities that are really just novelties but also a bit gloomy. Humans can fracture igneous rock to create sharp, curved edges. Evidence among artifacts associated with Stone Age man show that the first factories created by man were likely a collective effort to produce arrowheads, spear points, knife blades, and scrapers from a special igneous rock called obsidian. Today, obsidian blades are placed in surgical scalpels used in precise surgery settings. Studies indicate the performance of obsidian blades is equal to or superior to the performance of surgical steel. These people too were dabbling with the fundamental earth materials for a specific purpose, to find purchase by shaping rocks to gain an edge, to get above the ruck through individual mastery of a skill or intellection.

Some of the people whose job it was to prosecute the rules of childhood conformity were also my gateway to the thinkers who rejected the safety of neutrality and who understood the possibilities in the idea that calamity is what defines people best – or the best people – in a world where everything cannot be calculated, predicted and understood like a periodic table. These thinker-writers could be trusted to mean what they say and would never fear a thirteen-year-old would lose his luminosity at a funeral but would instead gain it with the crude energy of youth.

Nostalgic curiosity about Canada’s Yukon gold rush, combined with a poem’s powerful words and imagery, was probably my first experience with language’s power to scaffold a bridge between the actions that happen in the physical world and the energies and confusion of my emotional inheritance. I felt like a boy at the keyhole.

The Yukon region was the setting for an epic migration of men and animals propelled into feverish speculation. The world’s newspapers screamed, “Stacks of Yellow Metal!” The shack towns of Skagway and Dyea in Canada overflowed with novice prospectors unfamiliar with the killing cold. Until tramways were built late in 1897 and early 1898, the prospectors had to carry everything on their backs. The White Pass Trail was the animal-killer, as prospectors overloaded and beat their pack animals and forced them over the rocky terrain until they dropped dead. More than 3,000 animals died on this trail – many of their bones still lie at the bottom on Dead Horse Gulch. Robert Service, an English poet, became the voice of the region and an interpreter for a period that was marked by death and tragedy more than by riches.

Here is the first and last stanza of Service’s “The Cremation of Sam McGee”:

There are strange things done in the midnight sun

By the men who moil for gold;

The Arctic trails have their secret tales

That would make your blood run cold;

The Northern Lights have seen queer sights,

But the queerest they ever did see

Was that night on the marge of Lake Lebarge

I cremated Sam McGee.

“Midnight sun” is the first visual spark hinting that the work is alive with meaning. The irregular rhyme scheme of the poem approaches free verse, and a child can easily be enticed with all the action happening on the surface. But there is a deeply embedded narrative underneath Service’s story as the poem reaches through the fog and tinkers magically with language and imagery. The first stanza is a handshake with the reader, a salutation that is repeated again at the end of the poem as if to say GodSpeed: the words may drift out of range but the questions will remain. The poem’s internal stanzas approach the boundary line of reality and chaos – in a slow progression. The jurisdiction of the poetic form sustains the mystery of the ballad that seems to roll along with sing-song levity. There is contemplation (“promises are debts”) and writerly craft (“cold stabs like a driven nail”) that at once isolates the narrator’s voice and escalates the tension against the backdraft of a winter squall and men enraptured by the furious Yukon gold rush. The debt in this case has to do with a curious promise the narrator makes to an expiring Sam McGee, whose mania can rest only in the licking flames of a funerary fire. “Sizzle,” inserted fang-like near the end of the poem, describes the macabre sound of the cremation, and it is here that the plodding tale is thrust off the two-dimensional plane, right out of Service’s molars, out of the dark. With an ease of expression that belies the risk taken with such a poetic twist, the narrator’s lens snaps its focus on the secret locked within, in search of an understanding ear, and puts a demand on the reader to listen to the dead. This is where the ligature between what’s real and what’s “queer,” as it becomes flesh, as if to remind the reader of where the poem’s vital detail is lodged, in open possibilities and emotional extremities. With a sorcerer’s wit, Service chops down death with the tip of his pen.

Once ascended into the realm of pure fire, Sam McGee is more real than ever:

And there sat Sam, looking cool and calm, in the heart of the furnace roar;

And he wore a smile you could see a mile, and he said: “Please close that door.

It’s fine in here, but I greatly fear you’ll let in the cold and storm—

Since I left Plumtree, down in Tennessee, it’s the first time I’ve been warm.”

Service’s poem is carnivalesque, winter-demented, volcanically summoned, monstrous with fire and wild energy and, for me, unburdened by empty reactions like treating bleak childhood calamity with a glass of warm milk or a purchased adornment from a shop called My Sentiments Exactly or through empty rituals couched in symmetrical words like, “An outward and visible sign of an inward and spiritual grace.” Service’s cosmic lottery of destruction was looking for a way to get in, and the doorway fit us both, containing all the mystery, danger and opportunity. Fire and sword. Perhaps I could finally repair the timeline.

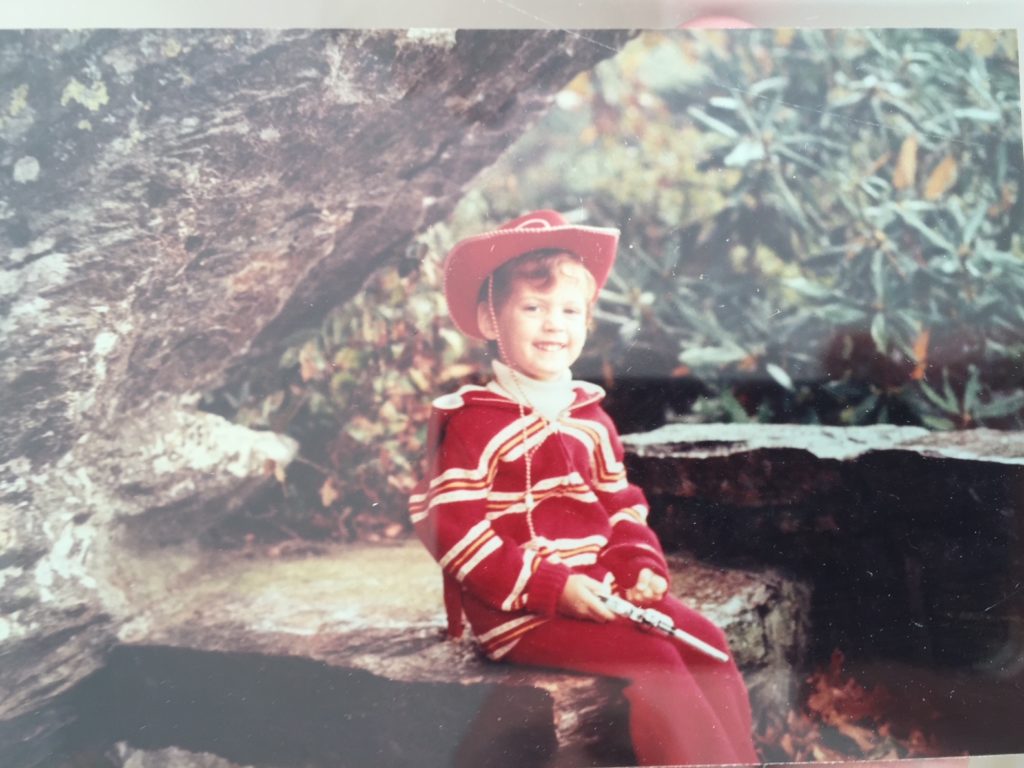

Me

The mine development plan was simply to get 100 million tons of phillipsite zeolite reserves under the yoke of human commercial creativity, one ton at a time, for the first time in history. I fanned out like the trade winds on a map, spreading indiscriminate fingers of commercial potential across vast distances, four continents even. The long haul to market started with samples of various sizes (1-2 millimeters, 3-4 millimeters and so on) sent via air freight for purposes of testing. Next we stuffed 30 ton shipping containers with zeolite in one-ton bags for large-scale in-situ evaluation. When crushed to a size or 1 to 2 millimeters and inserted into a bag labeled “Desert Rose,” zeolite delighted thousands of English cats in the form of a premium cat litter. The huge facial expression of a cat-loving child on the label betrayed the violence that was required to produce the stuff. This was my first and only experience with the $500 billion pet care industry that was in the nascent stages of pet “humanization” driven by higher spending per pet, per period. The truth is I preferred applying zeolite to living things rather than to the tail pipe of the cat food industry. In fact, when mixed with manure, it became a whole soil system whereby large patches of desert had youth and possibility inserted, and what came out was fierce green grass or tomatoes or flowers, and money potential.

The desert reclaims Plantation Dubai in the aftermath of scandal

One of Dubai’s more pizzazzful projects in which I supplied product was Plantation Dubai, a glamorous equestrian community concept built literally on sand and colossal extravagance, like desert estates with grand chandeliered dining rooms and adjacent air-conditioned horse barns and eighty million gallons of annual irrigation. From the single satellite image, the earthen patch pops out of the desert like a private garden in the fast lane of Dubai commerce. I later learned that the quick-witted Arthur Fitzwilliam, a stern-looking expat cut from proper British cloth, was evicted from the desert while angling the treacherous landscapes between prosperous and preposterous. Before there was a single horse or human resident, and before the ink had dried on his aceful Plantation Dubai CEO business cards, Arthur was arrested and vigorously questioned by some sweat-soaked forensic bureaucrats about the whereabouts of more than $500 million missing from company accounts and owed to Dubai Islamic Bank, which is the quivolent of owing lots of money to God. The two most contradictory elements in the universe are hope and abundant desert water. I am unsure where this guru of the grass-for-cash desert operation tipped into madness but the words, a “world full of fun and adventure,” are as good a meridian of his ambitions as any, a wild mouth on a word safari suspended on dust.

There is a global system of soil biology most of us are not aware of. And the fast lane of soil biology involved novel ways to recondition degraded soils and improving sandy soils to support animal and plant production. Intermediating in this space When zeolite is mixed with potassium nitrate, it fed thousands of Costa Rican banana trees until the growing trial ended upon Chiquita Banana’s bankruptcy filing, the day I arrived to access the trail’s performance, November 13, 2001. On that day, the company signaled doubt about repaying $862 million in debt, with the crashing of several Saudi-flown planes into the World Trade Center in New York City apparently decimating banana demand. Hope flared anew on the putting greens of many British Ryder Cup golf courses when our zeolite, reacted and mixed with ammonium nitrate, was inserted into the surface wholes created by a machine that excavated tiny pellet-sized aeration vents. And when crushed to a fraction of 30 microns (like talcum powder), it was demonstrated by a researcher at North Carolina State University, at the 95th confidence interval, our zeolite bound toxins (ie. removed toxicity) in animal feeds, thereby improving bovine yields. Tubes of zeolite powered intensive cultivation of strawberries in Saudia Arabian greenhouses, the output of which made a brief layover at the Athens airport to pick up EU-origin before reaching their final destination in posh London shops. I later learned the phyto-sanitary certifications were acquired illegally. There were bigger ideas too. Set against the mustard yellow haze of Earth’s lowest sunset and the mercurial waters of the Dead Sea, Abe, Jerry and I constellated fantastical applications for the zeolite. It even had trailblazing geo-engineering potential. Poured by the thousands of tons into the sea, in the gentle wake of lumbering container ships, a resulting algal bloom may have been capable of sequestering some of the world’s over-abundant carbon dioxide as the algae consume carbon dioxide, die, and fall to the sea floor with the gas permanently sequestered until the sea floor returns again to the surface as an island or maybe even a high plains desert. And enabling the soil to capture carbon through “rewilding” holds the potential to correct decades of over-serving the atmosphere with carbon dioxide.

The most adventurous elements of our minerals-for-cash ambitions would not happen. Concurrent with those sleepless nights at the Burj Hotel was the special angiogensis of tiny vascular pathways that were forming to supply cancer cells with oxygen and nutrients, like little meat hooks tearing at the flesh in the living bodies of Abe and Jerry. This ticking machinery would soon flare in near synchrony. Abe and Jerry would evaporate from my life. Abe’s chest imploded with cancer, his last breath a wind, and Jerry suffered swift neurologic decline that even I was not aware of other than through his disappointing silence. The cold gray-blue gunmetal sky coalesced with the hot red earth to produce for me the darkest clay, like an idea taking physical form, refining itself, becoming more essential and accessible before disappearing into the shifting dunes of black sand.

Private rocketry at my home – still sending things flying

Before I knew Abe or the action of industrial earthworks, personal fulfillment meant stirring up emotions in the people and friends in the neighborhood. My chronological story began there, in the moist, temperate woods of the Southern United States, behind my childhood home where I experimented with upward mobility by mixing small amounts of diesel fuel and ammonium nitrate as a way to cope with mild moodiness and urges towards rebellion. The organic boundary between subdued American suburbia and untamed forest seemed to me a natural place to speculate about chemistry. The peak of my early infamy coincided with lighting fuses in the wild. To the horror of the adults who were familiar with the schemes, I tooled the resulting detonations to bend the natural surroundings into conformity with my sensibilities. My senses swelled at the wild pulse of light, the amplified throb of earth, and the smell of sulfur mixing with the ripe organic decay of a forest absorbing my ambitions. What could be better than to blaze with all speed – and wild delight – away from the deep, primal vowel sounds breaking through the woods and then to witness smoke plumes, mushrooms even, twisting up through the gloomy moss and the thick canopy of majestic water oaks. With some luck, the police would arrive to quell the grief of a neighborhood briefly shattered. I heaved air into my stinging lungs, hiding out on the fringe of the action after a bolt of muscular propulsion. There were other forms of unbridled mischief, harmless spectacles that symbolized my angst with standing still too long. Then, I was more attracted to incubating innocent violence and placing sensitive elements next to each other, unaware of the risks of volatile reactions. I only wanted to prize up out of people and me some authentic spark, a sliver of Midnight Sun. I was creating my own earth out of the psychic geographies of my young mind and with it I got in touch with some interior place with sounds I could understand. I hammer-stroked into existence, with childlike lack of awareness, the people they themselves didn’t know. Rammed through the center of my childhood were rainy nightfalls, funerary ambiguities, plowed entanglements and indifferent ant armies dismantling fallen trees – together with a depth of feeling that I could not have known was connected to the force that would snake its way into my father’s DNA and provide the genesis of his leukemia. I remember wandering into the edge of the woods at dusk where giant-eyed summer Cedecas wailed with metallic urgency in a chorus of high-pitched undulating chirps against the infinite silence of the stars. The warm blanket inside my family’s house no longer made much sense to me.

Abe was an admired teacher and geochemist, a gravelly-voiced narrator of earth’s history, born into the landscape. He was gone, or I could say he was part of the earth, no longer a rock slinger, his biology now inserted like dust into the earth, his buoyant hints of mischief gone too. His mischief and curiosity were really about optimism and child-like play that was always honest. On other trips to Jordan I would drive out to see Abe at the Mars-scape mine site near the border with Syria and get into mechanical sympathy with the dusty production team: lumps of friable volcanic rocks, excavated by bulldozer from a two-million-year slumber, forced into the steely mouth of a hammer mill the size of a house. And then the upward thrust of dust. But today would be my last day in Jordan. I glided up the rutted driveway with an exaggerated slowness to show respect for the occasion.

Abe’s home is an artful, informal melding of concrete and wood that is a rare sight in a country with only one forest. Darting lizards, grinning dogs and far-off chicken sounds mingle in the breeze: cluck, crow, cheep, chirp. I had become so familiar with the feeling of permanent abundance surrounding the house and the garden and the orchard that the harvesting processes seems to betray the sense that the house now felt emptied of vitality. Inside, in the sanctuary provided by one roof, I could see the many weathered, funerary faces of Abe’s Bedouin family seated in the large room overlooking the fertile orchard scene. Feeling my way into this was the only way through. Inside, invisible lines of respect determined the seating positions of most of the mourners and revealed the social scaffolding I had only seen previously as faint signals among this family. Tertiary members stood in the rear. The oldest members sat in what can be described as the front row seats. In the center of the room, a large upholstered chair with hand-carved adornments and dense embroidery waited for me to undergo what looked like a litigation. The seating arrangement seemed too formal for these people, and I speculated that they too were unsure of protocol. This gathering was not the main event after cancer had liquefied Abe’s chest cavity, but it was special given the distance I had traveled and the measure of familial closeness in our friendship.

Outside a worker labors against the weight of a cart filled with ripe olives. They must have just harvested from the olive tree orchard, a sign of things not stopping. A goat wonders in the yard, the tiny bell around its neck tinkling in rhythm with the animal’s pre-slaughter indifference. Abe’s wife meets me at the entrance and, as we embrace, the tears flow, her wet eyes still smiling from the joy she believes Allah had gifted to her in the answered prayer of Abe’s love. For years I referred to her as Mom and she always treated me warmly, closer to something like a brother-in-law or first cousin, looping me in on the important decisions that involved Abe’s career and our project. For her this is the end of a life partnership, a gentle vice of earned love that emerged in adulthood after the blanket of a parent’s gift of love recedes. It’s quiet in the room except for the clanking of earthenware pots participating in the olive operations just outside the open window. The house was filled with the familiar smell of garlic and olive oil and baked bread. In Jordan, flashes of hunger always coincide with nutritional needs. Mom, the world needs more people like Abe – Abe’s son translates my words for benefit of the mostly non-English speakers in the group. Forty pairs of kind eyes look at me with approval and with the concreteness of operating room lights. I slowly made my way over to the appointed chair, shy about the evidence of my man tears, wondering whether Bedouins accept public male crying. There was a moment of long silence and hand staring. I tried to force relaxation by mentally recalling that there were no complicated areas in my relationship with Abe and his family. Simple questions were always met with direct answers. I could hear the whisperings of private, Islamic prayers, the treads of unity weaving through the room. There is a strange familiarity when a family of foreign voices are united in volume and tone. Then I am addressed by the eldest woman in the room. She had a permanently turned out lower lip and deep facial lines that were baked by decades of sun exposure. She gave off a counter-intuitive energy of being fully alive at 100 years old – and infinite calm. In Arabic, I discerned her kind welcome for me after my long journey to Jordan. She says she has one question. Abe’s son translates again. I nod in approval. Do you see this man sitting next to me? She points to her equally-ancient husband. Not sure what to think, I acknowledge with a slight head nod. He won’t stop complaining, she says,…will you take him back to America with you!? I’m stunned, what am I missing in this comment? My eyes probed back and forth looking for answers in the faces of the others sitting next to her. Without warning, a silent, gaping laughter peels down the old woman’s slender form like the ocean seizing the bow of a ship in a furious wallop of froth. Then the pulse of her words, a huge, wild invitation swarming and swelling, detonated an eruption of riotous group laughter, a contagion that twitched even the goat. When I tasted her words, the waters of her desert, they were like a sweet, deep-earth pyroclastic flow from deep time, and I cried with laughter in her true bliss, it having emanated from Abe’s spirit in this territory the old woman had created for us in that moment. Her spinning the axis mundi out of the ether was no doubt a tradition from her ancestors who inhabited those dry spaces that nurtured humanity out of rocks and dust. For a moment I got to know the heart of this tribe and the time-stretched feeling of belonging.

Even now I’m coming to know the dead as they fall into the past and at the same time I feel feel the groove of the road behind of me, the radiance of an inner landscape, and the future roads they don’t have that are mine now. They live inside of me like revolution, upheaval, my biographical rhythms torqued and also sheltered. I want to let loose the life’s cold grip of predictability, find a preposterous odyssey, and accept the only life worth living is the one I can barely survive, with small kernels of truth unearthed from these dead people, who gave me gold for my rust, who measured my heart first. What I learned most of all is to take all emotions as permanent equal partners in life, like a map of familiar patterns, and savor each one no matter the depths or the heights, fire or ice, because a life filled with the satisfaction of greedy impulses or pizzazzful narcissistic expressions contain nothing but the hollowness of a desert or the chafe marks left by a velvet rope. These emotions and memories contain intelligence locked up in the messy biology of living. I want to get out there and play and get dirty again and melt into the forces shaping my external reality.

Abe collecting rocks